A SIDE, hook, a lil’ preview of the remix

“I can see a little Horton in you.”

The observation caught me by surprise: there were two possible resolutions to what the ballet instructor meant.

Either 1) I bore a striking resemblance to the elephantine Dr. Seuss character.

Or 2) She somehow knew I took Horton Technique dance classes at Alvin Ailey Extension last summer.

Considering the last Horton class I took was in early July, I was about to be self-conscious about my size until she continued, “It’s wonderful to have someone in class with modern dance experience!”

How, I thought, could she have possibly recognized the vestiges of a technique I had only just begun to learn nearly a year earlier, with little practice since?

That the practice lingered over time and space within my body and through my movement challenged me to reconsider not only the material reality of movement but also the seemingly more abstract practices of reflection, practice, and inscription.

The reconsideration reminded me–

It has been almost exactly one year since I started this blog–meant to serve as a personal place for reflection and transcription. But meant to transcribe what?

Thoughts onto paper

Feelings into sentences

Movement into pictures

Experiences into analysis

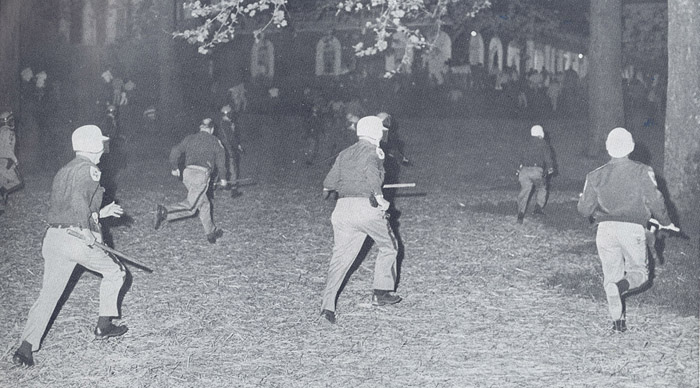

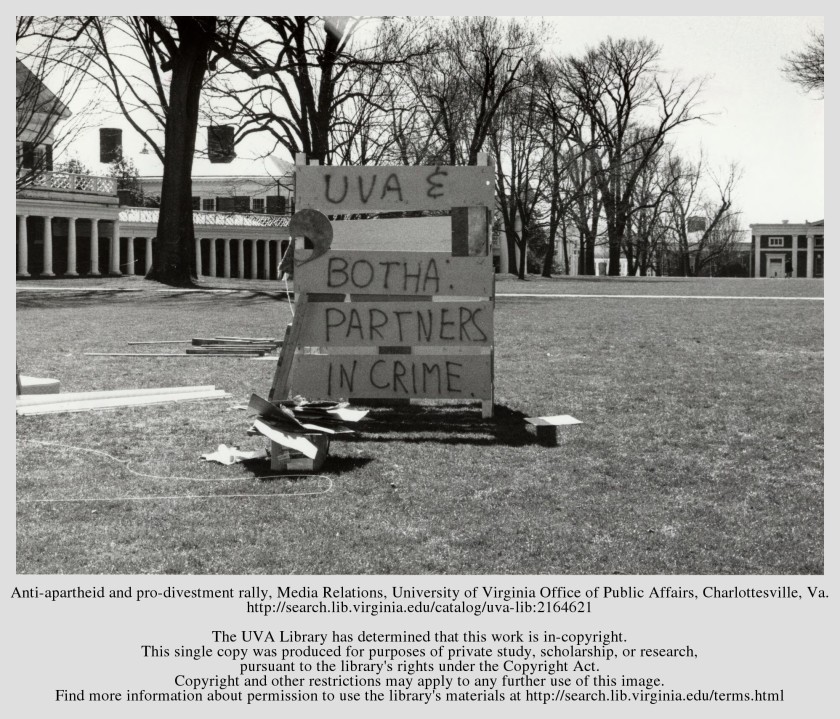

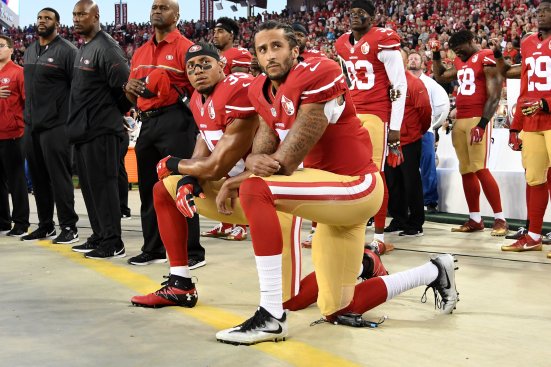

There was a process…perhaps even a processing, that helped me at times, such as when the Klan marched on August 11th and 12th in Charlottesville.

If the blog’s primary purpose was to “process” the corporeal into the literary, one might argue that it merely reinforced the preconception that there is a distinction between what is read and what is actualized through movement.

Literatureisvisceral?

A bold assertion made as a thesis unto itself that what fell under the header was an automatic automotive–words that moved and performed via my written performance of engagement with text and performance. Perhaps I hoped that readers would simply be too lost in the theoretical reversals to recognize the consistent medium of presentation remained literary.

Back to text, back to text, back to text.

Text which is legitimate in academic circles and legible to english speakers.

Text which can appear without the body which, when dismembered, is reappropriated.

What began as a project fundamentally about my body so quickly lost it.

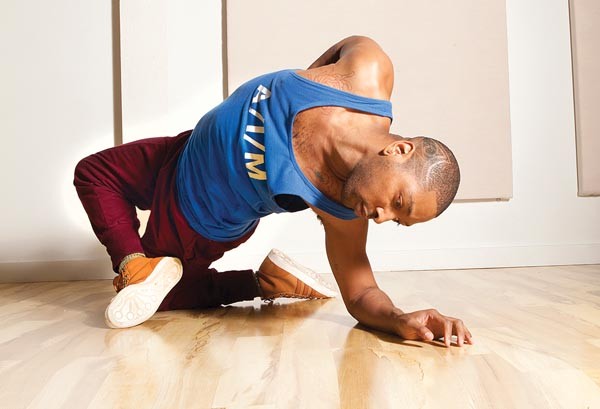

Backbreak, SWAP, The reprise: bouncebouncebounce….

“I struggle to put these thoughts on paper–thoughts that run barefoot through the recesses of my mind. They bump and collide and b-b-back up like atoms in my DNA…”

Lights up, four dancers enter, two from the voms and two from the upstage wings. They walk miscellaneously, bodies twitching with unrecognizable vagrancies until lights focus in warm spotlight.

One of the dancers, a young woman, stops faced forward. Her right hand covers her mouth in silence. The stage lights are warm on her brown skin.

A long pause.

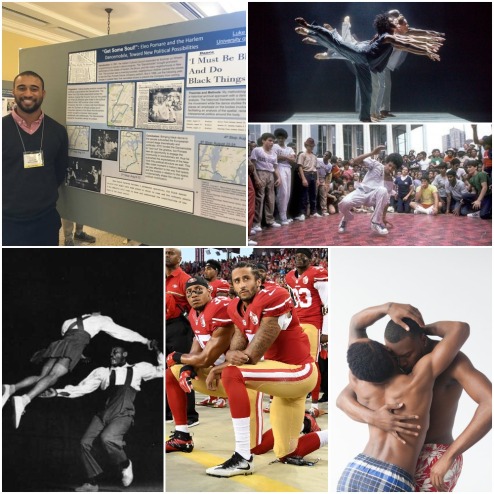

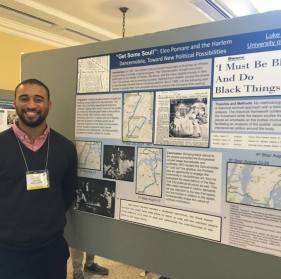

Theory, a piece I created and performed for the University of Virginia Spring 2018 Dance showcase.

Everything my thesis needed to be but couldn’t, Theory was.

It moved. There was no argument. It was assembled more so than it was choreographed–each member contributing their unique movement style to the piece. The body arrived with the text.

bouncebouncebounce….

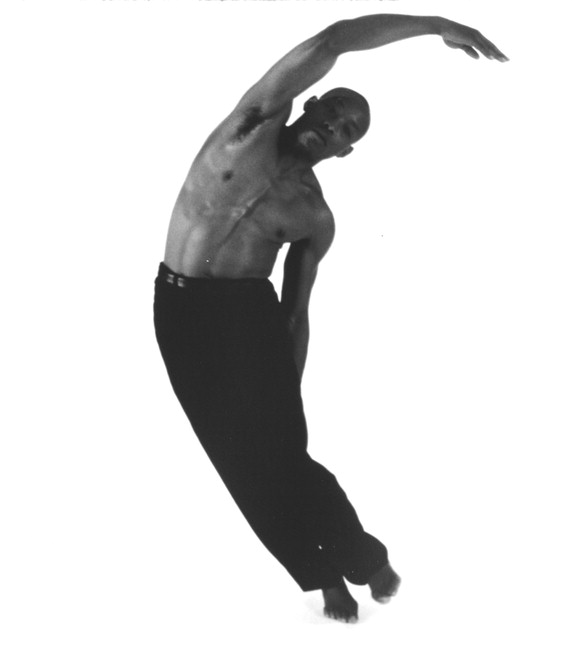

The idea for the staging was first planted when I watched video clips of the Bill T. Jones / Arnie Zane Company performing Story / Time. The blend of the spoken word and the moving body, relegated the written word to an afterthought while recognizing that language and movement are blended together rather than in opposition.

It reminded me of watching a video lecture in class that was performed, yes performed, by Susan Leigh Foster. A dance scholar, Foster intentionally blurs the lines between the written word and the moving body. Though it might seem as though her rendition is meant to “bring the words to life,” I sense that it is an acknowledgment that the words are already alive–that there is a vitality to words that often goes unrecognized unless merged with a form that is already tied to the body, such as speech or dance.

I have a hunch that an emphasis on knowledge through the written word rather than the knowledge of the body is an aftereffect of colonialism, but that’s not quite my interest here.

Here, I am interested in the growing case for the concomitance of the literary and the corporeal, and specifically, the methods for translating between the two.

It might best serve my purpose to propose variations of mediating between the perceived distinct planes:

For example, if a journalist must capture movement for the sake of a newspaper, they must transcribe the body onto a page in the form of a written word.

Inscription on the other hand might be the manner in which words are made evident on the body. In the same way words can have flavors, tastes, and sounds which are used to create colorful imagery for an author. The experiential effect of words, phrases and meanings might linger in one’s body.

Rather than thinking of the body as a metaphorical text or tabula rasa upon which one inscribes experiences for a deterministic constructionist approach to the body, I think one ought to think of the body as the site of negotiations among these inscriptive forces. Thus we recognize the word as something corporeally powerful but also that the body is an active negotiator of experience.

Interlude: Out of the abstract for a moment…

Graduation from the University of Virginia this past May has been an opportunity for reflection. As graduates attempt to sign, seal, and deliver the summation of their four years experience, often boiling it down to a social media picture with a pithy phrase, the atmosphere is a performance of mediation.

Not only a mediation between generations that rivals the awkwardness of and family reunion, but also a mediation of the graduate body that attempts to translate their inscriptive experiences back into a transcriptive form for their celebrants.

Common phrases include:

“How can I possibly capture my four years here?”

“I am the summation of my friends and our time together!”

“I have taken so much away from this place.”

And in my own reflection, “How does this experience translate into the next?”

“How did this experience translate from the last?”

A question I also asked when I found myself back in Dallas for the St. Mark’s School of Texas graduation ceremony.

As I stood in the back of the celebration, I was struck by the similarities it bore to my own graduation from high school four years earlier. As we did, the class of 2018 walked past–young men off to begin their four years at many distinguished universities.

For me, the metaexperience was a reflection on an inscription as I remembered my own feelings walking down the sides of the graduation seen and past my parents. Of course, at the time, I didn’t know, and could not have known, the tumultuous events that lay ahead at the University of Virginia. All of them inscriptive forces that defined my experiences, though not exclusively, and not entirely.

Attending the commencement ceremony made me feel a bit like Tom Sawyer attending his own funeral, though not as morbid, certainly. But the voyeuristic moment of reflection in which he sees the otherwise inaccessible moment creates a queer occularism that bends space and time. It makes for an opportunity to reflect on that which has not happened, and so exist from two vantage points simultaneously.

Standing on the commencement green, I felt something similar by looking back to 2014 and thinking about myself at the time. It was an opportunity to think about inscriptive factors at the time and over the next four years that looped back into the present moment. “Who was I then, and who am I now?” In a nutshell.

Reflection had become an inscriptive force in itself as memory, distorted by time, affect, and inscription itself, continuing its ability to change experiences past, present, and future.

What of the blog then? A place of reflection that actively inscribes my present and future bodies as I write it, read it, and reflect upon it. Experiences transcribed return to inscribe, demonstrating how tenuous the artificial lines between literary and corporeal realities are.

Literatureisvisceral.

The Exitlude:

Well, shoot. Here we are folks. The last post for this project.

Next year I will begin a new blog to track my projects, perhaps it will be more or less research oriented. It will depend on what I need at the time, in reflection, on what this platform has been for me thus far.

My hope now is that as this link floats around in the interwebs it will occasionally collide with someone, and in so doing reiterate an inscription for them. There is a chance that my body and its experience will be felt in the words, transcribed, so that they may be inscribed into someone else.

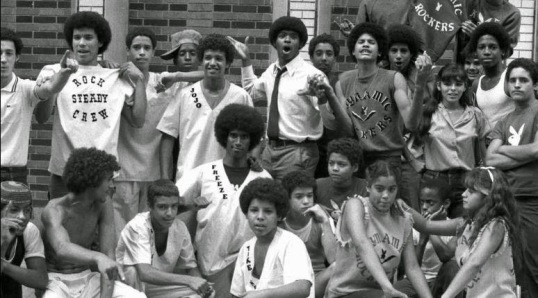

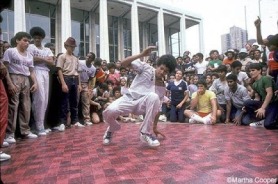

Well, it went terribly. My plan only carried me through the first few seconds, then the music changed, so my steps were off the bass beat. The intro to the new songs began with some sampled vocals that made my hard two-count stomping seem absolutely ridiculous. Not to mention that I had been so focused on my feet that my hands were frozen at my sides. What kind of dancing incorporates a lot of hands? Voguing, yes voguing! Which might have worked if I knew how to vogue. Instead, I flailed a little bit, hopped around one foot, then my sunglasses flew off my face, so I tucked tail and shuffled out of the circle as the bass kicked in for the new song. It was embarrassing, and my cousin got the whole thing on video.

Well, it went terribly. My plan only carried me through the first few seconds, then the music changed, so my steps were off the bass beat. The intro to the new songs began with some sampled vocals that made my hard two-count stomping seem absolutely ridiculous. Not to mention that I had been so focused on my feet that my hands were frozen at my sides. What kind of dancing incorporates a lot of hands? Voguing, yes voguing! Which might have worked if I knew how to vogue. Instead, I flailed a little bit, hopped around one foot, then my sunglasses flew off my face, so I tucked tail and shuffled out of the circle as the bass kicked in for the new song. It was embarrassing, and my cousin got the whole thing on video. Then I noticed that he was signaling at me with his right hand. First pointing to the sky with a boney finger, then two thumps over his heart, followed by a final point at me. He repeated this cadence twice before I realized that he was giving me props for dancing in the circle. I signaled back by beating a fist over my heart with a bowed head. He smiled, and the crème suit man turned back to the circle to watch the next dancer who had already dove in.

Then I noticed that he was signaling at me with his right hand. First pointing to the sky with a boney finger, then two thumps over his heart, followed by a final point at me. He repeated this cadence twice before I realized that he was giving me props for dancing in the circle. I signaled back by beating a fist over my heart with a bowed head. He smiled, and the crème suit man turned back to the circle to watch the next dancer who had already dove in.